This blog has been going nearly seven – count them – not that it’s all that much effort to count them – unless you’re really bad at counting – although, thinking about it, that “nearly” does make it a bit trickier, so maybe the last one’s a sort of “seve” rather than a “seven” – years. And this is my 1,251st post, which means... well, it certainly means, although whether it means anything in particular. Maybe that I missed some sort of milestone in the last post? Dunno. Anyway, yes, right, and in that time, well, woo, hasn’t everything changed? Well, not really, give or take a few iPhone models. But this blog has changed, and so has blogging as a whole.

I mean, back in those oldenny timey days I had no shame in doing compendium posts on any number of only tangentially related subjects, usually ending with an arbitrarily chosen picture or YouTube clip; and everyone would weigh in with their contributions and contradictions and corrections and it was, as the sainted Patroclus called it, one big conversation; but then something happened somewhere along the line; and I’m still blogging, but Cultural Snow seems to have turned into a continuum of discrete articles, each about a subject. And plenty of people are reading what I’m writing (I don’t know if it’s more or less than it was in the old days, because I’ve only had the magic thingy wotsit that tells me how many people are reading for the past three years) but far fewer are commenting.

I mean, back in those oldenny timey days I had no shame in doing compendium posts on any number of only tangentially related subjects, usually ending with an arbitrarily chosen picture or YouTube clip; and everyone would weigh in with their contributions and contradictions and corrections and it was, as the sainted Patroclus called it, one big conversation; but then something happened somewhere along the line; and I’m still blogging, but Cultural Snow seems to have turned into a continuum of discrete articles, each about a subject. And plenty of people are reading what I’m writing (I don’t know if it’s more or less than it was in the old days, because I’ve only had the magic thingy wotsit that tells me how many people are reading for the past three years) but far fewer are commenting.

So, if I were blogging now under proper old-style blogging conditions (only one substitute allowed, two points for a win, highlights later on Match of the Day), I’d probably have some choice words for Booker judge and all-round silly sausage Peter Stothard, who said of the rise of literary bloggers:

Eventually that will be to the detriment of literature. It will be bad for readers; as much as one would like to think that many bloggers’ opinions are as good as others. It just ain’t so. People will be encouraged to buy and read books that are no good, the good will be overwhelmed, and we'll be worse off. There are some important issues here.

...to which I’d point out that bloggers are simply people with opinions, just like professional literary critics and that while there are doubtless some literary bloggers who are a bit crap, anyone who tries to argue that every paid literary critic on a highbrow newspaper or magazine knows what s/he’s talking about is either arrogant or stupid or probably both. And then I’d point out that criticism is no longer (never was, to be honest) about a select few handing down verdicts from above; it’s about argument and dialectic and kite-flying, and about how very often a statement can be wrong, but can still have value because of the intellectual fireworks it provokes in others; and I’d probably remind my readers that this is what Stothard is saying is pretty much what Andrew Keen said, and Keen was talking bollocks as well. But it doesn’t matter because between them they’ve prompted me to say something far more sensible, which is how this whole thing works, so thanks guys, you bloody imbeciles. And this would have been pretty much par for the course, because looking back, we didn’t half blog a lot about the nature and purpose and meaning of blogging.

And that line of argument would sort of trail off a bit, and I’d start talking about how I don’t much like the sound of Steven Poole’s new book, which appears to argue that because he’s not that interested in food, we shouldn’t be either. And then I’d remember that I was quite rude about his previous book as well, and then felt very guilty because he was subsequently very generous about my Radiohead book, but in fact I didn’t feel guilty, it was just an excuse to squeeze in a mention of my Radiohead book and maybe some of the others.

And that line of argument would sort of trail off a bit, and I’d start talking about how I don’t much like the sound of Steven Poole’s new book, which appears to argue that because he’s not that interested in food, we shouldn’t be either. And then I’d remember that I was quite rude about his previous book as well, and then felt very guilty because he was subsequently very generous about my Radiohead book, but in fact I didn’t feel guilty, it was just an excuse to squeeze in a mention of my Radiohead book and maybe some of the others.

But then I might have changed tack completely and reflected on the most recent episode of Dr Who, with its scary cherubs and time paradoxes and, ooh just a little splash of Dennis Potter, maybe. And then I’d ponder the metafictional nature of Melody’s pulp novel, with its plot lines that the characters are doomed to follow, which rather obscures the fact that the characters are really doomed to follow the diktats of Steven Moffat, who wrote the script. And I’d ask whether the Doctor cheated by reading the chapter headings, whether they exist in advance of the action or in parallel to it.

And I’d make a clumsy effort to pull together various elements of the above (blogging and self-aggrandizement and postmodernism, basically) and suggest once again that you really ought to be reading my Infinite Jest blog, in which I am currently exercised by David Foster Wallace’s cavalier attitude to chapters and chapter headings. Oh, and snot. There’s lots of snot going around.

And then I’d say, yay! That Rockmother’s blogging again!

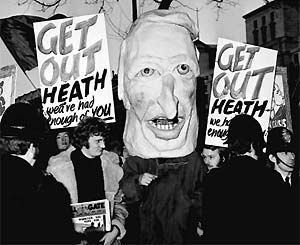

And finally I’d probably put in a picture of Helen Mirren and/or Charlotte Rampling not wearing very much, but still tasteful, like. OK, Helen it is:

But of course I won’t do any of that, because we don’t do that old-style blogging any more, do we?