When I was young and thin and floppy-haired and given to spouting Situationist one-liners while wearing my late grandfather’s trilby and drinking tequila, the book we were all talking about was If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller, by Italo Calvino. This was a piece of metafiction, a novel that acknowledged and drew attention to and played about with its own fictional status. You could tell this from the off because the first line was “You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino's new novel, If on a winter's night a traveller.”

Of course, metafiction wasn’t new, even that long ago; think Tristram Shandy, Don Quixote, back to The Odyssey and probably even earlier than that. But once you’ve had your eyes opened to it, you see it in the unlikeliest places. The example I always use to explain it is this reaction shot from the movie Trading Places, where Eddie Murphy doesn’t so much demolish the fourth wall as tap it lightly for a moment, just to remind you it’s there. In fiction, it seems to drift in and out of fashionable acceptability. Douglas Coupland, David Mitchell and Jennifer Egan have had fun with it in recent years, but champions of earnest, caring seriousness such as Jonathan Franzen disapprove of such japes. And there appears to be a worrying new trend opening up somewhere between the two schools of thought, where it’s acceptable to write 95% of a serious, straightforward, linear novel with a beginning and a middle and no characters who share the author’s name and then in the last few pages to say, look, sorry, all that stuff you were just reading? All that emotional investment you made? I didn’t really mean it. It was Just A Story. Now, where’s the invitation to Hay? It’s as if metafiction has been degraded, from an attempt to challenge complacent literary conventions, to a lame punchline, the and-then-I-woke-up ending that’s taken an MA in creative writing. The revolution went backwards; Elvis joined the army and all we were left with was Pat Boone and Cliff Richard. Yann Martel did it in Life of Pi, as did Jonathan Coe in his most recent, deeply disappointing effort, The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim.

But the big one was Ian McEwan’s Atonement, in which a good chunk of the plot is revealed at the end to be a self-redeeming fiction created by a novelist suffering from dementia. Whereas Calvino or Sterne would be happy to introduce the befuddled writer at an early stage, drifting in and out of the narrative, challenging and cajoling the reader who might be expecting a nice little country house potboiler, McEwan doesn’t trust us. We have to be fully absorbed into the world of the characters or we may just jump ship. In fact, it would be quite feasible to read the book without the dénouement.

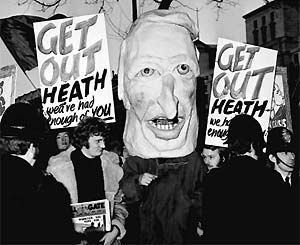

Atonement did very nicely, thank you, and they got a big movie out of it, but you would have thought McEwan might have got the whole metafiction thing out of his system, or alternatively had the guts to write a metafictional narrative that was upfront from the first line. Instead, he’s written Sweet Tooth. On the face of things, it’s a spy thriller. The most obvious debt is to John le Carré, but most specifically to the recent movie version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, because McEwan really piles on the early-1970s period detail; le Carré didn’t bother, because he was writing in the 70s, so he didn’t need to discuss Ted Heath and the IRA and the three-day week and Jethro Tull. It wasn’t period detail, it was now. (In the acknowledgements, McEwan thanks several of those pop history books about the 1970s that everyone was reading at the end of the Noughties, when they should really have been reading about the Noughties. Just thought I’d mention that.)

Although Sweet Tooth shares the glum griminess of le Carré’s Circus, McEwan’s protagonist Serena Frome is far down the pecking order from George Smiley et al. Rather than overseeing deep-cover agents in Moscow or Belfast, her role is to headhunt and subsidise writers whose work might provide intellectual heft to the western, anti-communist cause, without them realising they’re effectively MI5 stooges. Serena loves books, especially novels, although parental pressure contributes to her reading mathematics at Cambridge (and getting a third) rather than the Eng Lit degree she should have taken. This gives McEwan the chance to place in her mouth disobliging remarks about postmodern jiggery-pokery and how she favours more conventional narratives. “I said I didn’t like tricks, I liked life as I knew it recreated on the page,” she declares. And:

I suppose I would not have been satisfied until I held in my hands a novel about a girl in a Camden bedsit who occupied a lowly position in MI5 and was without a man.which is followed by a dig at Borges and Barth. We also get walk-on parts from literary big hitters of the time, including Martin Amis, Angus Wilson, the publisher Tom Maschler and the editor Ian Hamilton. But McEwan doesn’t write himself into the plot (as Amis did in Money), presumably because that would tip off the reader that something funny was going on. Tom Haley, the author that Serena inveigles into her scheme (and with whom she embarks on an evidently doomed relationship) clearly has some similarities with the novelist, not least his background at Sussex University and the content and style of his short stories; although the novel that makes his name seems to be a reworking of The Road, albeit one written 30 years before Cormac McCarthy had the idea, which takes us into Death of the Author territory. The combination of all these nose-tapping hints suggests to the alert reader that there’s something clever-clever coming along at the end, which makes it feel even more like a gimmick. I won’t spoil things if you’re going to read the book, but just remember that one of the central characters is a novelist. OK?

McEwan can still write of course. The first line of his first book is still one of my favourite opening gambits: “In Melton Mowbray in 1875 at an auction of articles of ‘curiosity and worth’, my great-grandfather, in the company of M his friend, bid for the penis of Captain Nicholls who died in Horsemonger jail in 1873.” And that skill hasn’t deserted him in Sweet Tooth: “Arguing with a dead man in a lavatory is a claustrophobic experience.” But it would be nice if he remembered how to tell a story; and to have the guts, where necessary, to tell us that he’s telling a story from the beginning, rather than leave it as a lame, postmodern punchline.